What does your hashtag look like? Lee Rainie from Pew Internet Research - Episode 17

Scott and Marc speak with Lee Rainie from Pew Internet Research about the new report Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters and how its findings can be used to better understand and grow online communities.

- Lee Rainie - Director, Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project

- The six types of Twitter conversations by Lee Rainie

- Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters By Marc A. Smith, Lee Rainie, Ben Shneiderman and Itai Himelboim

- Conversational Archetypes: Six Conversation and Group Network Structures in Twitte By Marc A. Smith, Lee Rainie, Ben Shneiderman and Itai Himelboim

- NodeXL

- Tools for Transparency: A How-to Guide for Social Network Analysis with NodeXL

Transcript

David McMillan: I’m David McMillan. I’m the developer of Sense of Community Theory, and this is the Social Media Clarity Podcast.

Lee Rainie: The greater the diversity of information coming in, the more that people are inviting in newcomers and new perspectives, the healthier they become.

Randy Farmer: Welcome to the Social Media Clarity Podcast, 15 minutes of concentrated analysis and advice about social media in platform and product design.

Marc Smith: Thanks for joining us on this Social Media Clarity Podcast, I’m Marc Smith.

Scott Moore: I’m Scott Moore.

Lee Rainie: I’m Lee Rainie.

Marc Smith: Our guest this week is Lee Rainie from the Pew Research Internet Center. Welcome Lee.

Lee Rainie: Hi Marc and Scott.

Marc Smith:It’s good to have you here. Tell us a little bit about the Pew Internet Research Center. What do you do there?

Lee Rainie: We are primary research folks who take money from the Pew Charitable Trust, it’s a big foundation, and turn it into research about major forces in American culture. I look at the role of technology in people’s lives. There are other parts of our center that look at people’s political situations, peoples religious situations, their demographic realities … We do global polling as well, so it’s a pretty eclectic mix of subjects, and we do it without trying to advocate for anything. We are not funded to change the world, we’re funded to understand the world.

Marc Smith: What are the highlights of those changes that your research has uncovered?

Lee Rainie: Well, we’ve looked at three big revolutions that have occurred in less than a generation. The first was the internet broadband revolution. When we first started doing survey work, hardly anybody had broadband at home.

Now 70% of American adults have broadband at home, and it’s changed the way they use the internet, think about the internet. It’s certainly changed the way they think about being content creators themselves. They are very much more involved in their culture and their communities because they have the capacity to speak in ways that they never did before.

Second big change that we marked was the mobile connectivity revolution. As people got smartphones and then tablet devices, they became very different kinds of social communicators, and their relationship to information changed very dramatically as they could get it anytime, anywhere, on any device that was connected. That’s been hugely transformative of people’s access to information and to each other.

The final revolution is the social media revolution itself. It’s just really impacted people’s lives that they can see their social networks in action. They can promote themselves to their social networks, and they can engage with folks who matter to them, both their weak ties and their strong ties, in new kinds of formats. The persistent, pervasive, awareness of social networks has also had dramatic changes in the way that people think about engaging the world.

Marc Smith: In many cases you’re doing survey research and you’re asking people questions on the phone or in email, sometimes on the web. Are there other directions that you’re exploring as you explore the social media landscape?

Lee Rainie: One of the obvious things that we saw in the data from the earliest days of looking at social media, is that people’s social networks, the people they consider friends and acquaintances, are actually a pretty important person variable in people’s lives. Those who have bigger networks and more diverse networks, are really different people from those who have smaller networks and more tightknit networks.

As we watched how important it became to people that they could access their networks, and act on information and things that they learn from their networks, we wanted to look for new tools about measuring networks because the survey methods that have long been used to assess people’s networks are very limited.

You can only ask people about a certain number of friends in their life, and what they do for you, and what you do for them. You run out of time pretty quickly, so in an era where people have hundreds and hundreds of others in their social networks, new tools seem to be useful to map that.

That’s what brought me into the world of the Social Media Research Foundation in NodeXL. It was performing the exact function that I was hoping that it would, which is to explain networks in new ways and understand what they meant to people, with a very new tool that was not based on survey work.

Marc Smith: Right. There was a report recently that Pew released, maybe you could describe some of the high order findings of that research publication.

Lee Rainie: I think it was you, Marc, who came up with the notion that we could look at all these maps and begin to act like archeologists, or zoologists, and at least see the basic structures that began to emerge as we looked first at hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands, of maps.

Literally, it was a human based scan of all of these maps that we were doing to look for patterns, and it was so interesting to see that one of the patterns that was evident early on in our mapping was the polarized political pattern that had already been spotted in the blog link networks of the early 2000’s.

It was fascinating to see there were 5 other structures that dominated the conversational styles that were taking place on Twitter depending on the topic that was discussed, depending on who were the influencers driving the topic, depending on the information that was being shared in the networks.

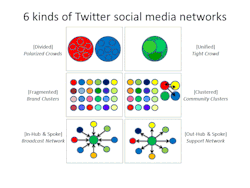

We ended up basing our report on the fact that there were six fundamental conversational styles that were evident in this mapping tool on Twitter. One was polarized crowds, another was the exact opposite of polarized crowds, very tightknit groups, then there were brand clusters, where folks were quite dispirit and disengaged from each other in talking about things, even though they were talking about the same subject.

There were then community clusters, where often it was the case on a big international news story, where lots of news organizations were talking about it. You could see communities break apart depending on the news sources they were using. It looked like a bazar where clusters of people were coming together to talk about the things that mattered most to them.

Finally, we saw two different kind of hub and spoke networks. One was kind of a broadcast network, where a prominent person, a prominent organization, essentially was broadcasting to its followers. It was a single central node where it would tweet out information and lots of people would tweet it to others, but wouldn’t necessarily talk back to the original source. That was a sort of center to the outlying regions structure.

Then there was an outlying regions to the center structure that we called the support network, and lots of corporations have support staff monitoring Twitter to see who’s talking about their products. We could see lots of people communicating into the center from the outlying regions, into the center, and the hub and spoke structure was flowing in a different direction. Six different kinds of structures, having six different kinds of conversations, in very different contexts.

Marc Smith: With these six different patterns in mind, if you were a social media manager or host, how do you think that this report could be applied to their practice? What would they do with it?

Lee Rainie: Well, the first thing is to orient yourself. One of the most fundamental, cartographic, powers that exist in tools like this is you can figure out where you are. Just literally doing mapping of who’s talking about you, who you’re dealing with, who’s following you, who’s passing along information about you, is an enormously useful tool.

Again, these maps tell a very different story than the basic metrics of how many retweets you get, or how many people come to your webpage, or stuff like that. This is about community structures, and as we’ve seen in our other kinds of research, the social aspects of information are now the central aspects of information.

People understand where they fit in the world, and understand where they are based on how they deal with their social networks. Just figuring out where you are through these maps is its own virtue, but then you could look at other mapping structures and see, maybe there would be some advantages.

If you have a tightknit community, maybe you want to add people to the community and figure out ways that you can become relevant to folks outside the tight cluster that you exist in. There are ways that you can now test how to do that, see how much progress you’re making, try out different strategies for expanding your reach.

By the same token, if you’re in a polarized cloud structure, maybe you think it would help your cause if you could bring in new allies and to figure out other kinds of techniques, or information strategies, to get your information outside your tight crowd. To get it to people who might be useful in sharing it to the folks on the other side of the aisle who might be open to it if it came from different voices.

There are plenty of ways that you can see how businesses can expand, community managers can grow their groups, community managers can measure engagement, and things like that. These maps are wonderful testing tools for that.

Marc Smith: In some of the maps, Lee, you see what could be called community, and not all of the maps have it. Could you describe the difference between a part of a Twitter network that is a “community” and the parts that are clearly not a community?

Lee Rainie: The vivid demonstration of that in these maps is the tight crowd structure. As you look at what is being tweeted, and who’s tweeting to whom, and who’s linked to whom, you just see this tight network of connection, affiliation, friendship. People know other people in the community. People are comfortable with others in the community. They’re deeply linked to others in the community, and the map just clearly demonstrates how tight, and circular, and affirming, this kind of structure is.

Scott Moore: This is great because this I think gets to one of the things that I want to understand better. In the communities that I see, it’s not often that everyone is talking about, or to, everyone else. That there are clusters within that, there are cliques, they overlap. Where does community start to shift over into one of these other network maps?

Lee Rainie: I don’t think we see any hard and fast rules about community formation, and expansion, and dispersion. It really is topic dependent. It’s partly dependent on the nature of the social structures themselves, and it’s partly dependent on the season of the year.

There are some times when certain topics are hot, and some community members dominate the conversation, or have lots of things to say, or are the most interesting ones to talk to, and then things move on … Another topic takes over, another series of voices becomes dominant.

What you really get out of these maps is a sense of fluidity in communities. It’s not always the same people doing the same things, its people doing different things at different times, with some variance in whose dominating conversation, what type of information is dominating the conversation.

To the question of when does this tightknit structure give way to other structures, it’s partly a function of adding new members, new topics, and new sensibilities to the community. In many cases it can be driven by, literally, new members joining the community.

They add new stores of information, they add new experiences, they add new perspectives on some of the things that community members are talking about, and you can maybe watch the evolution of the group sort of embrace this new information, or say this is outside the boundaries of what we want to talk about, or the way we want to talk about it.

Communities have lots of decisions to make about how much new information to introduce. Of course, the literature on this is very rich. The greater the diversity of information coming in, the more that people are inviting in newcomers and new perspectives, the healthier they become.

Of course, there’s a tipping point where it’s too much new stuff, too many new people, too little connection, and the community struggles for that. It’s often the case that communities get too tightly wrapped up and are not too terribly hospitable to newcomers, and that can be a hindrance and a boundary to growth, and a boundary towards figuring out new stuff, in new ways.

There all sorts of norms and practices, and experiences, that shift around depending on the way that communities are structured in the first place, and then depending on the topics that they want to talk about.

Marc Smith: The only thing I’d add is, yes, a network might have a corner with dense community, and another corner with lots of fragmentary disconnected people, and that both of those can exist under the same rubric, under the same topic, in the same discussion. A network analysis could admit both of these, that you could see, yes, we have a lot of people who are disconnected, but yes, there is this core.

Lee Rainie: Neither is right, nor wrong. It’s just that both can be additive to the community experience, and both can go off the rails and be horrible under the wrong circumstances. What these tools are teaching us is that the communities can have these shifting, fluid, structures with different pockets of activity going on at different times, and that’s just in and of itself sort of interesting to behold.

Scott Moore: I actually would like to go back up higher level, just because I’m curious about this question for the Pew Research. How is network analysis going to inform future Pew reports and surveys?

Lee Rainie: My long-term dream is to have that baked into virtually everything that Pew does in the way of surveys, but even if I don’t get my dream realized, these new tools, starting with NodeXL, but other kinds of social network mapping tools as well, they just shed light on aspects of the human condition that surveys sometimes don’t do a good job exploring.

In a way, this might be complimentary to the things that you can discover in a survey. You don’t necessarily have to bake it into surveys. You can definitely enrich the stories that you are telling from survey data by adding to it. These are the folks who are talking about it in these particular ways.

Americans, for instance, want to understand the role of polarization in our political process and how destructive it might be, how defining it might be, of politics. You can ask people lots of questions about that and get thoughts of impressions, and things related to their views on polarization, but there’s nothing more vivid than seeing those polarized clouds in the Twitter discussion, to show you what’s become of American discourse.

In a way, it gets back to my point that it compliments, supplements, adds new material, to the things that you can figure out when you ask people questions.

Scott Moore: Thank you so much, Lee, for talking to us today. I think getting a broader view of the impact of social networks, and social network analysis, and how we understand our world is a great insight, and I really appreciate you sharing that with us today.

Lee Rainie: It’s been wonderful to see how this work has relevance to lots of folks, and I’m delighted to hear that it works for your crowd too, Scott.

Marc Smith: This was great stuff.

Randy Farmer: For links, transcripts, and more episodes, go to socialmediaclarity.net. Thanks for listening.